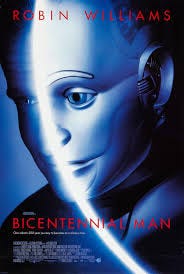

For years now, I’ve shown the film Bicentennial Man in my Human Nature course. I tuck it right between the units on souls and the meaning of life, near the end of the course, because I think it’s a great transition between them: the reason why there’s even a question of whether the main character Andrew is human is that his life clearly has meaning and it’s really easy to believe that he has a soul as a result.

The movie is based on two stories by Isaac Asimov. Here’s a quick synopsis: Andrew the android is a robot purchased by the Martin family. The robot is meant to be a housekeeper and general assistant. But it turns out that he has emotions and creativity, and when he discovers this, Richard Martin encourages Andrew to pursue those things. Richard even becomes a sort of tutor/mentor for Andrew to learn the ways of humanity. Eventually Andrew asks for and is granted freedom. Over time, Andrew becomes more and more like a human, including physically, because he invents artificial organs that can be implanted into real humans and, over time, he rebuilds his own body with them. (Yes, there are ship of Theseus issues here, but he keeps his “positronic” brain the whole time, so we’ll ignore them.) By the end of the film, he has fallen in love with Richard’s great-granddaughter Portia, and wishes to be recognized as fully human. He even takes steps to become mortal as part of this quest.

I use the film to prompt students to think about what really makes us human. This takes place about 85% of the way through the course. By then, we’ve discussed our animal nature, how to understand self-interest (individualistically or relationally), reason and emotions, and bodies and souls. I ask students to consider which of these human qualities Andrew has by the end of the movie. The main observation is that although his biology is functionally human—his body functions the way a human’s does—he isn’t a biological animal and doesn’t have DNA. We discuss whether this is necessary for being counted as human, given that he has many (arguably all) of the qualities that make us count other humans as persons: morally important beings who deserve our recognition (by which we mean roughly respect and care).

The students are understandably uncomfortable with calling Andrew a human. I ask them why they think he wants this status so badly. What’s at stake here? I also guide them to make a distinction between humans and persons—humans are the animals with particular DNA, and persons are morally significant beings, a broader category which would include all the intergalactic intelligent species in, for instance, Star Wars and Star Trek—and ask whether they think Andrew would be happy being counted as a person but not a human. (This is debatable in the context of the film.)

At the end of the class, I have them vote on Andrew’s humanity the way the World Congress does in the movie. Most of the time they vote against his being human. I suspect that’s because they’re more comfortable calling him a person once they have this distinction; this gives them an easy out that the World Congress didn’t have. If they didn’t have this distinction, I’d bet the question would be harder and the vote closer.1

For a long time, I was somewhat puzzled by this. I really wasn’t sure why the biology mattered so much to them. I was ready to count him not only as a person, but a human, largely for Turing Test kinds of reasons: you functionally couldn’t tell the difference without cutting him open, so why draw what feels like an arbitrary line?

This year I understood better. The advent of “artificial intelligence” in the form of large language models that can produce text that sounds like it’s coming from a real person pushed me back in the skeptical direction. These bots are only doing statistical prediction. There’s no connection to truth or the experience that a biological organism has. The computer behind the language is what has come to be called a “stochastic parrot”: something that makes guesses (“stochastic”) that mimic human language (“parrot”). Knowing about LLMs—and moreover, the outsized claims and ambitions about intelligence and rights their creators have for them—has made me much more hesitant to accept that (a) such a thing as Andrew could be created, and (b) any robot could actually have the kind of intelligence that would merit the status of personhood.

But. There’s an important difference between Andrew and an LLM. He’s embodied—and becomes more so as the story unfolds. He has referents for the words he learns. He has sensory input that shapes his interactions with the world, thus allowing the world to shape him. He gradually develops emotions, which are another sort of information processing, not the same as conscious logical reasoning. It seems plausible to think that he’s got embodied cognition2—as the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it, “the central claim of embodied cognition is that an organism’s sensorimotor capacities, body and environment not only play an important role in cognition, but the manner in which these elements interact enables particular cognitive capacities to develop and determines the precise nature of those capacities.” The fact that he’s embedded in and interacting with the world makes a significant difference to how we should understand him. So in the end, LLMs should not make me more skeptical of Andrew’s personhood than I used to be.

Now, the human brain—or even the brain of a smaller mammal, bird, or reptile—is bogglingly complex. The problem of other minds remains, and although in everyday life it makes tons of sense to assume that other humans (and animals) have minds, the presumably very different basis of cognition for a robot would raise questions we don’t need to grapple with in the case of biological organisms. I have no idea how realistic it is that an Andrew-like robot could be developed someday. I rather hope it isn’t, because that will bring with it all of the hard questions about consciousness and rights that the film grapples with. But hey, that would make it clear why philosophy matters!3 (And also science fiction.)

Occasionally we have time to re-vote using personhood instead of humanity, and that vote usually comes out in Andrew’s favor. This is not surprising.

I realize that this term is not technically used correctly, given that “embodied cognition” is really a theory or approach to research, not a thing entites can have. But I think the language is illustrative, so I’m using it.

I literally jumped for joy two years ago when a student—unprompted!—actually said this in class.